Scientific Principles of Strength Training

Written by The Boostcamp Editors

Mastering Scientific Principles of Strength Training

Many factors determine what should be your best approach to strength training, including but not limited to: your experience with training, your genetics, and the amount of time you are able to allocate to training. With all of this being said, there is an undeniable importance to the structuring and detailing of your training to achieve the greatest level of progression. In the context of resistance training, a few important variables to consider are the scientific principles that empower you to create effective training programs and make informed answers to tough training problems for a lifetime. One such principle is specificity, which refers to the idea that training should be tailored to the specific goals and needs of the individual. By incorporating exercises and training methods that closely mimic the desired outcome, you can maximize the effectiveness and efficiency of your strength training routine. Adjusting training based on gender, experience, abilities and other factors is the final principle needed to optimize training. Differences will exist both as Inter and Intra Individual Differences and will affect an athlete’s Maximum Recoverable Volume.

Resistance level - amount of strain (in terms of weight) exerted on your muscle

Volume - number of reps and sets

Exercise Type - Selected exercise type

Exercise Order - The order with which you lift

Rest intervals - between sets and training days

Training frequency - how often you are targeting each muscle group for training

As you can see, there is a lot to get into with this topic and the details of each factor can quickly become very dense and technical. The goal of this article is to introduce you to some basic ideas for a basic theoretical understanding of what you are doing, and to summarize some evidence-based principles that you should think about when structuring your workout. References will be listed along the article, and we encourage you to dig further if you desire a greater understanding of the science behind muscle mechanics and physiology!

Chad Wesley Smith, a top 10 raw powerlifter of all time, has co-authored the book "Scientific Principles" with Dr. Mike Israetel and Dr. James Hoffmann, providing a unique combination of scientific and practical knowledge in the field of strength training. This book is widely regarded as one of the most comprehensive resources available on the topic of building strength. Scientific Principles goes far beyond just giving you sets and reps to use for a few weeks or months, rather it will empower you with knowledge to create effective training programs and make informed answers to tough training problems for a lifetime.

Basics of Muscle Movements

Let’s first talk a little about something that is seemingly simple - what are your muscles actually doing when you are lifting? An intuitive answer may follow along the lines of ‘flexing’ or ‘pumping’ the muscle, but what does that actually mean? To begin answering this question, we must define the 3 basic types of muscle contractions:

Concentric - Typically understood as the ‘contraction’ of the muscle being targeted. The muscle fibers contract and shorten the muscle in question, exerting a force on the resistance, typically against gravitational force.

Eccentric - Typically understood as the lengthening of the muscle targeted. The muscle fibers lengthen relative to their resting position, and the movement is usually in the direction of gravity, with the resistance weight running in the same orientation

Isometric - Where the length of the muscle is unchanged, as the forces exerted on the resistance and gravitational pull are equal and thus the muscle/body does not move during the course of the action.

Examples of the 3 types of muscle action may be exemplified using the bicep curl. During a simple bicep curl, when the dumbbell is lifted upwards towards your chest, you are lifting the weight by contracting the bicep muscle fibers, moving the dumbbell against gravity. Under this movement, the biceps undergo concentric action.

Resistance is still exerted on the dumbbell as you lower the dumbbell, slowly moving it down towards the sides of your body. As the biceps remain in tension and lengthen after the contraction, this constitutes an eccentric action.

Finally, if you use your biceps to pull up on a bar that cannot be moved, you are placing the biceps in tension without causing any sort of motion, and would thus be a stationary, isometric action.

Optimizing Exercise Types

Studies have shown a few ways to use this understanding to our advantage when building muscle. For instance, there is greater force per unit of muscle size produced in eccentric action, but less motor unit activation at same tension, which is critical for optimal muscle hypertrophy.

Related to this, exercises can generally be divided into single or multiple-joint movements; leg extension and bench press are common examples of a single and multi-joint lift respectively. The clue is in the name - single-joint movements only involve movement relative to a single joint in the body, and thus considered more stable and less injury-prone. On the other hand, multi-joint movements are more complex as they involve movement in more than one joint, and generally involve greater muscle mass activation. While both types of movements have their role in a well-balanced workout routine, multi-joint exercises are generally regarded to be more effective for gains in strength, and elicits a greater short-term metabolic and hormonal response from your body.

A general rule of thumb is that the energy demands and testosterone response that follow exertion are directly proportional to the muscle mass involved in the exercise. Therefore, movements that engage a larger group of muscles in the body over its range of motion (squats, deadlifts, power snatches) will be more physically demanding, which in turn should lead to more effective muscle stimulation and growth. This is the reason that many of the most popular programs that you will find on Boostcamp and the internet - such as the 5/3/1 workouts, PHAT, and PPL-based programs - are often anchored on the so-called 3 major lifts: bench press, squats, and deadlifts.

Structuring Your Workout

Exercise order also matters! There is consensus that multi-joint, compound exercises performed at greater intensities should be done initially during a workout session. Lifts that involve a myriad of muscle groups and have a large range of motion are not only more physically demanding, and require a lot more physical and mental coordination to execute with the right form and cadence. As such, much of your effort as you start your workout journey should be ensuring that you nail down the fundamentals of these compound lifts, as much of your initial progress will be tied to your progression in these exercises. With the challenges that these factors pose, your risk of injury is also generally higher and more potentially serious. Ordering your workout to tackle compound lifts first will ensure that your muscles and attention are as fresh as possible to perform these movements safely and with the best form.

We previously mentioned that multi-joint exercises are the most effective at stimulating growth in a large group of muscles, so saving your strength to perform compound lifts at a higher intensity is your best bet for gains. If you start your workout with isolated exercises and move on to compound lifts when you have already begun to fatigue your muscles, meaning you won’t be squatting or benching with a potentially higher intensity, you are often leaving growth margins on the table. Remember to always prioritize your physical and mental strength for compound, multi-joint exercises.

The ordering of targeted regions is also important to keep in mind - in general, it is recommended that you rotate opposing exercises during your workout. What does ‘opposing’ mean? Well, that depends on the type of workout you are following. If you are doing a full-body workout, opposing could be alternating between upper body and lower body lifts. If you are doing an exclusively upper or lower body day, opposing would mean the use of antagonistic muscles, like alternating between push and pull lifts or working your hamstrings and quads. Interspersing your workout in this way can give your muscles a short amount of time to recover between targeted exercises, allowing you to take on a greater load, putting increased strain on the muscle over the entire length of the workout, thus optimizing growth.

The Basics of Weight Training Progression

Like our primate ancestors, humans have a fairly strong muscular structure. But why do we even have muscles to start with? Evolution tells us that early humans were likely selected for good muscle density, given the hunter-gatherer structure that early human groups relied on. In this context, fitness refers to your body’s ability to adapt and maintain a state that is advantageous for survival - while having good upper body strength likely has little impact on your ability to perform your desk job, it was literally a matter of life and death for our ancestors. If your survival demands a certain level of muscle fitness, your body’s ability to harness nutrients and grow your body constitutes that historical and biological foundation of what we now call strength training. Our modern attempts at bodybuilding remain grounded in our biological history, and science has helped us develop more effective muscle growth regimens as we become more knowledgeable of our biological history and their underlying processes.

As the name suggests, progression in a workout system refers to the gradual advancement towards a particular goal. In the context of resistance training, this would be an increase in muscle strength, endurance, and mass. This is largely done via adaptation, where the body is consistently put into a certain level of stress, which stimulates growth in order to habituate to that level of exertion. When we speak about progression, the term progressive overload may come to your mind. This is an important concept, so let’s explore this further. Strategically changing exercises and loading strategies is critical to avoiding injury, staleness and maximizing long term success. Variation can be created through Loading Strategy, Exercise Selection and Tempo, the proper use of these elements will allow us to satisfy Directed Adaptation without running into Adaptive Resistance. Stimulus Recovery Adaptation (SRA) is a guiding principle in organizing training into an effective sequence of providing stimulus and allowing your body to recover from and adapt to that stimulus. Understanding and properly applying the Principle of SRA will help you optimize the Frequency of your training.

Fundamentally, progressive overload is what the term suggests - a progressive increase in intensity, ever closer to your body’s tolerance threshold. However, these parameters are not standing goalposts, but rather shift in accordance to your body’s fitness. As you begin to build up strength and mass, lifts done in the same intensity and frequency will not exert the same amount of stress on the muscles as they have become stronger and more tolerant to that same level of stimulus, improving your tolerance threshold. As you grow muscle fiber, a greater proportional resistance or rep range will be needed to reach an equivalent level of exertion. However, barring anything substantially outside your range of tolerance, your body actually quickly adapts to a certain routine, and a program that consistently increases in intensity, such as hard training, is the most efficient for progression.

In short, progressive overload can be incorporated into a routine by:

Increasing the load of the particular lift

Increasing the reps of each set

Doing more sets of the same lift

Speed of executing the lift

Shortening rest periods between sets

Often, a combination of the above will be included in any well-designed protocol that applies the principles of progressive overload.

How Your Nervous System Helps you at the Gym

Many of you may have had the following experience: after consistently hitting the gym for a couple of days, you may find a certain load to be more manageable than from a few days ago. This may have been encouraging - your muscles are growing! However, it is unlikely for there to be meaningful muscle hypertrophy that leads to an appreciable gain in strength over the span of a couple of days. If so, your body seems to be doing more with no ‘physical’ changes in muscle mass. How is that possible?

We now know that this is due in large part to smart adaptations by your brain. Lifts can be termed stereotyped movements, in that they are relatively simple movements performed repetitively. When the body is constantly performing the same movement, your nervous system will find ways to optimize your performance. Studies have now shown that more transient increases in muscle strength are related to increased muscle fiber recruitment by the central nervous system, meaning your brain learns to incorporate more muscle fibers into a movement, effectively using more resources at its disposal to handle the same load. The same study has also shown that imagined movements, mentally rehearsing an action in your mind, causes increased excitability in the corresponding motor area of your brain’s neocortex. Some have also hypothesized that increased nervous system coordination means your actions are more well-integrated into the entire motion range of the lift, leading to better joint integrity.

The above is part of the reason why it is important to have focus at the gym, and do slower reps to get a feeling for the lift in its full range of motion. By doing this, you are giving your brain time to learn how to use your body in the most effective manner, boosting your rate of progression and general physical competence. This highlights that resistance training is not only making changes at the level of your muscles, but also the neurons that connect your muscles to the spinal cord and your brain. Many seasoned lifters have been shown to have disproportionate improvements in muscle strength that correspond to little muscle hypertrophy over the span of years, further supporting the notion that you are not only working your muscles at the gym, but training your mind to take better control of your body.

Where to Find a Good Strength Training Program

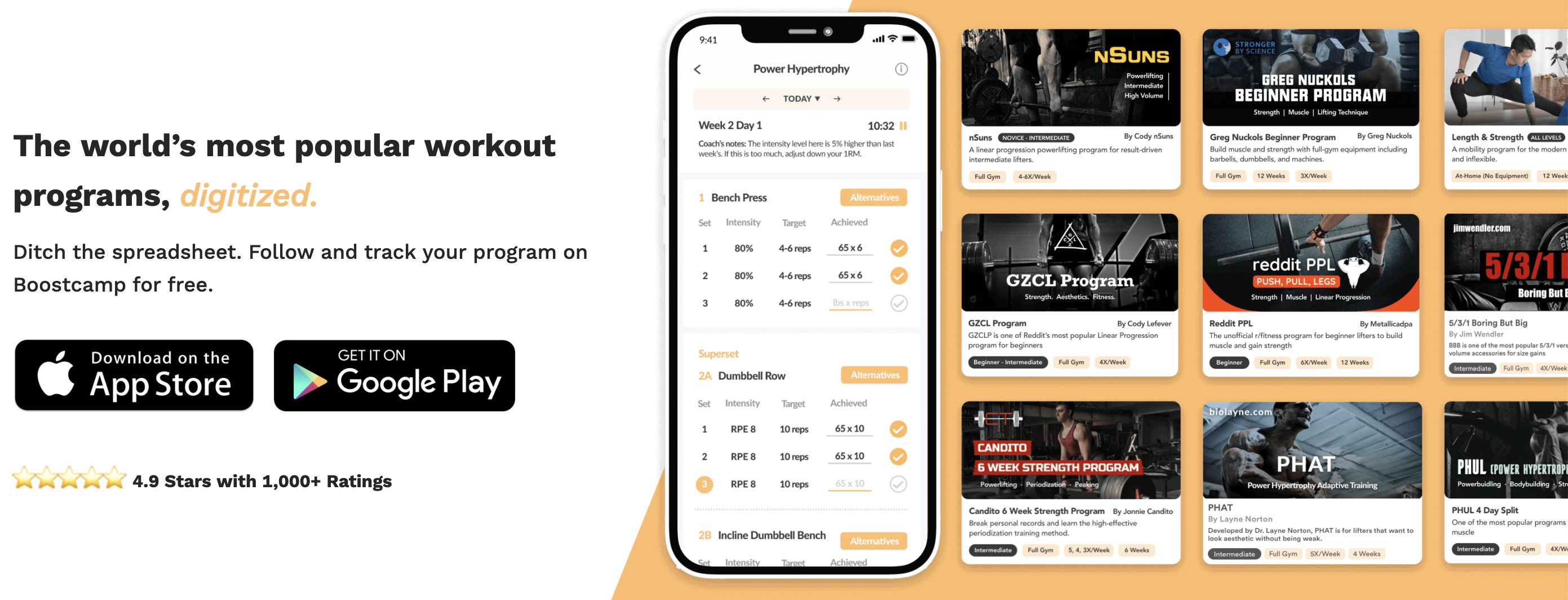

When it comes to finding a good strength training program, you can look right on the Boostcamp App! The Boostcamp App houses over 50 free workout programs from world class coaches. You are able to choose a program that is pre-written, such as a push/pull/legs split, or an upper/lower split. However you can also create a program, and most importantly, track your progress!

Scientific Principles of Strength Training Conclusion

We hope that this article introduces you to some basic resistance training concepts, and motivates you to do some research by yourself as you begin your workout journey! Make sure to check out our other blog posts for more general workout information, in addition to detailed guides for your curated programs - all of which can be found for free on the Boostcamp app!

Let us know! And be sure to follow Boostcamp on Instagram and subscribe on YouTube!